After a year in Japan I had it pretty much figured out. After two years, it was more like I had Japan halfway figured out. After four years, I’d finally graduated to understanding that I really didn’t know anything.

That was probably more of a ‘growing up’ thing than something special about Japan. But the truth is that one society rarely fits into the categories created by another.

My own interest began when I was a kid, most likely from You Only Live Twice and Toho movies about giant monsters. As an angry teen balling my angry little hands into angry little fists I was drawn toJapan’s history of aestheticized violence, exemplified by the samurai and the ninja. And with nothing else to give me direction, I majored in Japanese language and literature in college. Naturally Japan stopped being about throwing stars and Godzilla.

Instead, my interest started to revolve around the schism between Japan’s history and its modernity; changes in the West that spanned centuries became part of Japan’s late 19th Century rush to modernity (or Westernization) with no time or space for reflection. Japan’s horrific turn with fascism, a nostalgic madness that exterminated millions (more than the Nazis in fact; look it up), left a kind of existential desert for future generations.

And with my degree, my canvas bag of Nikons, and an unshakeable faith in my own correctness, I was going to capture the beauty and pain and make the generation-defining photo epic just like my hero Robert Frank had done in 1950s America.

That didn’t happen. Of course.

After teaching English for a year and working in a factory for three more, I went back to the States with nearly 1000 rolls of developed film. I quickly found that all of my peers were four years ahead of me in getting their lives figured out, and I felt like a lost child pretending around grown-ups. Those 1000 rolls went into a box and I concentrated on trying to become a photojournalist. Years passed. Then a decade. Then in 1999, in Buffalo NY, I dove into my contact sheets, made choices, made scans, and some 35,000 images became about 1200.

I often tell people that photography is a meal where you have dessert first. You can’t really make 200 oil paintings in a day, or make 20 sculptures, or write five novels, but with photography it’s very easy to amass thousands of images in a few hours (I routinely come back with more than 2500 images after shooting a wedding). The real work is in the editing.

Which, finally, brings me to this body of work.

“Chanbara” is a term for Japanese swordfight movies, based on an onomatopoetic for the sound of two sword clashing together (-chan!-). Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and The Seven Samurai, the Zatoichi and the Lone Wolf series, are all chanbaras, as are elements of the Kill Bill films.

With themes of violence and alienated individuals effecting bloody justice, they are culturally similar to Westerns in the US and there is a history of cross-pollination between the genres. Akira Kurosawa loved and copied John Ford. Two of his movies were then remade as Westerns (Sergio Leone had a print of Yojimbo on set when he made A Fistful of Dollars, and The Seven Samurai was remade in Hollywood as The Magnificent Seven). That said, are often much darker than American action films; instead of violence preserving the norm, violence is the norm. And while in American films the protagonists, having defeated whatever evil, can return to society, to families, to their homes, the protagonists in chanbara, whether they chose this world or were cast into it, cannot leave.

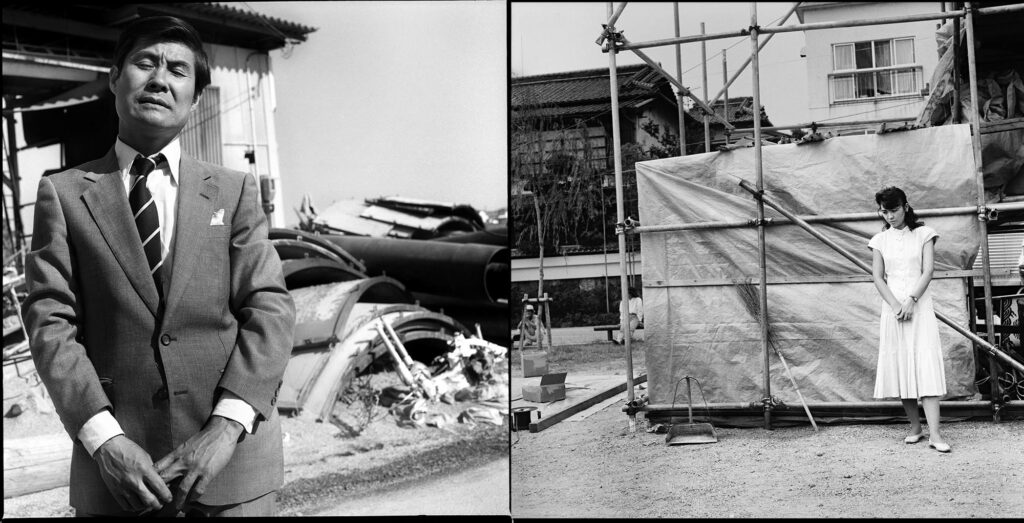

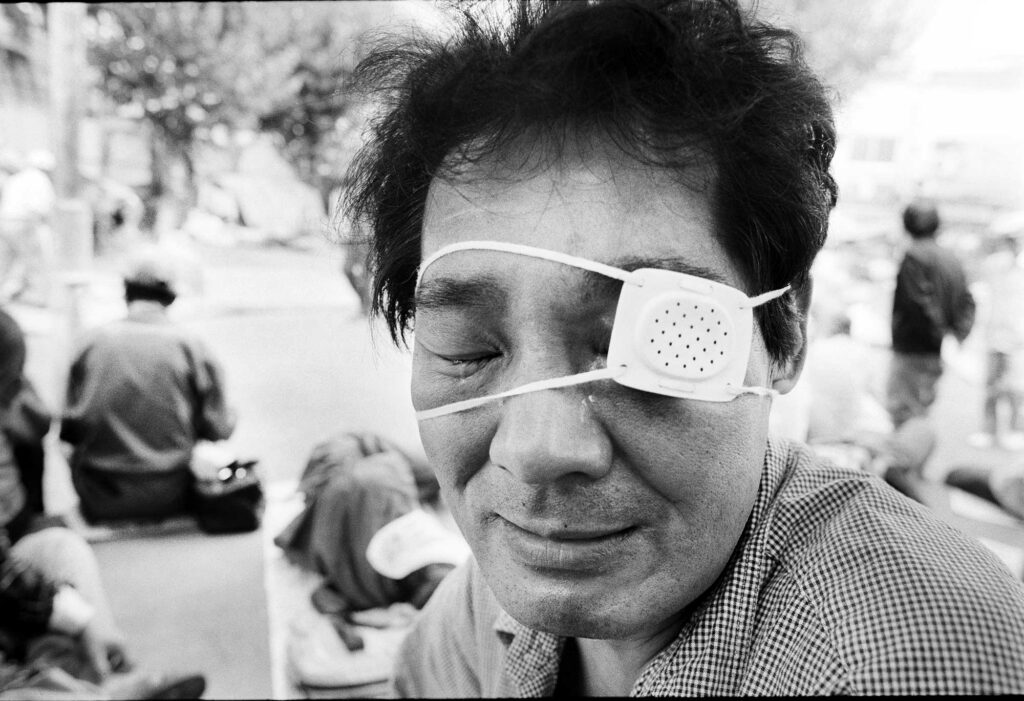

I put Chanbara together to examine how the division of men and women into separate worlds creates a mutual estrangement. I’m most interested in how masculinity has been tied to militarism and violence, how this confining mindset has victimized women, and how it ultimately leaves men with brutalized psyches and damaged bodies.

The rise of fascism in the 1930s and the devastation it brought, continues to cast a shadow in the form of the ultra-right wing uyoku. Like many other ultra-right groups, it manifests a hyper-masculine identity through a fictionalized vision of the past. Fueled by alienation from the cultural changes following 1945, they seek a return to the ideals of the samurai era, restoration of Japan as the dominant military power in the Pacific, and racial purity within Japan. It is not at all uncommon to see their refurbished buses, covered with flags patriotic slogans, moving through the city blasting sidewalk-vibrating military music through PA speakers.

So… that’s what I made.

Living for a time in a society different from where you grew up in doesn’t make you a citizen there, it’s more likely to make you a stranger in both. In a perfect world (in my perfect world..) someone would look at my work, understand it, and come away with a reinforced belief in my brilliance. But in this world, the truth is that a lot of what I am doing requires some context to make any sense.

And that’s why I’m doing this.

I am not the man who shot these photos. That was more than half my life ago. But I am the man who chose these photos, and comparing the distance between these two people helps me understand who I am and the world I live in.